Biting the Big Apple

Jonathan Marcos

Abstract

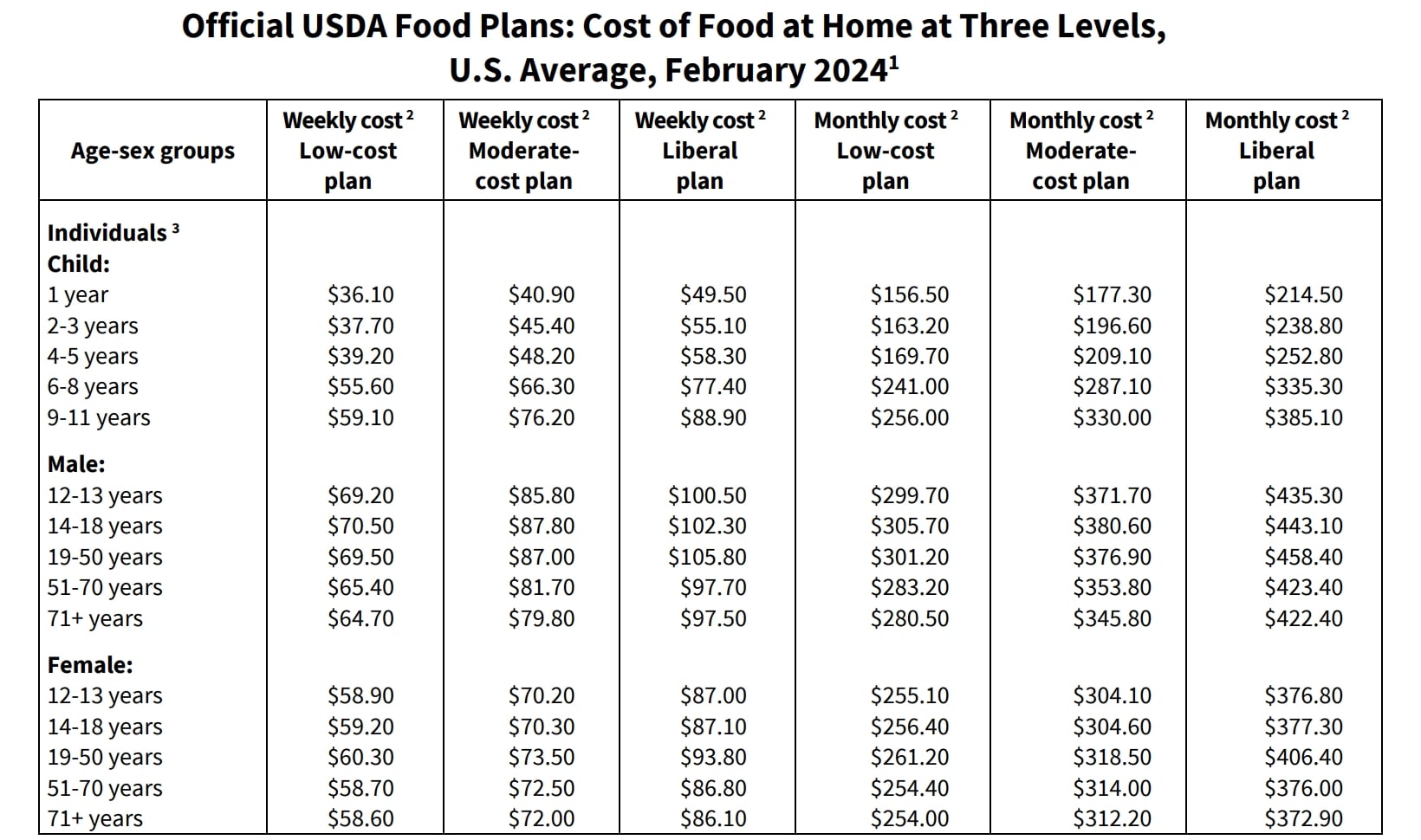

The USDA recommends that individuals spend at least 280.95 a month on average to afford economic, healthy meals. Per USDA statistics, 10% of a household’s salary should be invested in order to purchase these meals comfortably, estimating that an income of 33,714 USD is necessary.

In the context of New York City's 196 neighborhoods, 82 of them make an average median income less than this threshold. In these neighborhoods, more than 225,000 people are dependent on some kind of food assistance program in order to comfortably afford meals. Though this encompasses only 2.5% of people in the city, the number is still fairly large– greater than the populations of cities such as Yonkers and Richmond. Food insecurity makes individuals more prone to malnutrition, resulting in increased risks of high blood pressure, diabetes and other diet-related health problems.

Admittedly, this only scratches the surface– there are far more variables that encompass what makes a neighborhood food insecure. Biting the Big Apple will go through a comprehensive deep dive of New York City’s food insecurity, elaborating what food insecurity is in the context of NYC, where food insecurity is most prevalent, why it is important to address food insecurity, what does food insecurity look like, and how food insecurity can be tackled throughout the city.

What is Food Insecurity?

Food insecurity is the inability to comfortably access affordable, healthy dietary options. In the context of New York City, it takes two forms:

Food Desert: Areas that have both poor proximity to healthy food options and also cannot afford it

Food Swamp: Areas that have good physical proximity to healthy food options, but populace has difficulty affording it

On the contrary, there's also:

Food Oasis: Areas that have good physical proximity to healthy food options and where populace can afford it

In incumbent investigations by the USDA, food insecurity is mostly emphasized by the lack of physical proximity (10 mile radius) to a supermarket. However, since NYC is so dense, the term "food swamp" must be used to discuss the lack of economical access to healthier options. In order to truly discuss which neighborhoods are riddled with food insecurity, various investigations and correlations of data such as income, supermarket and bodega counts, median rent and vehicle counts are all correlated to paint NYC's food insecurity landscape.

Where is the Food Insecurity?

In order to get a comprehensive understanding where food insecurity is most prevalent, it is essential to take in data from various sources. In these investigations, various infrastructural datasets (i.e. supermarket counts, vehicle prevalence) are correlated with various economic parameters (i.e. Average median income, food stamp prevalence) to identify conditions of what makes a place food insecure.

Based on these results, three different neighborhoods will be chosen: one food oasis, swamp and desert. These areas will be investigated further in a qualitative manner, completing the definition of food insecurity that the numbers in these quantitative presentations cannot articulate.

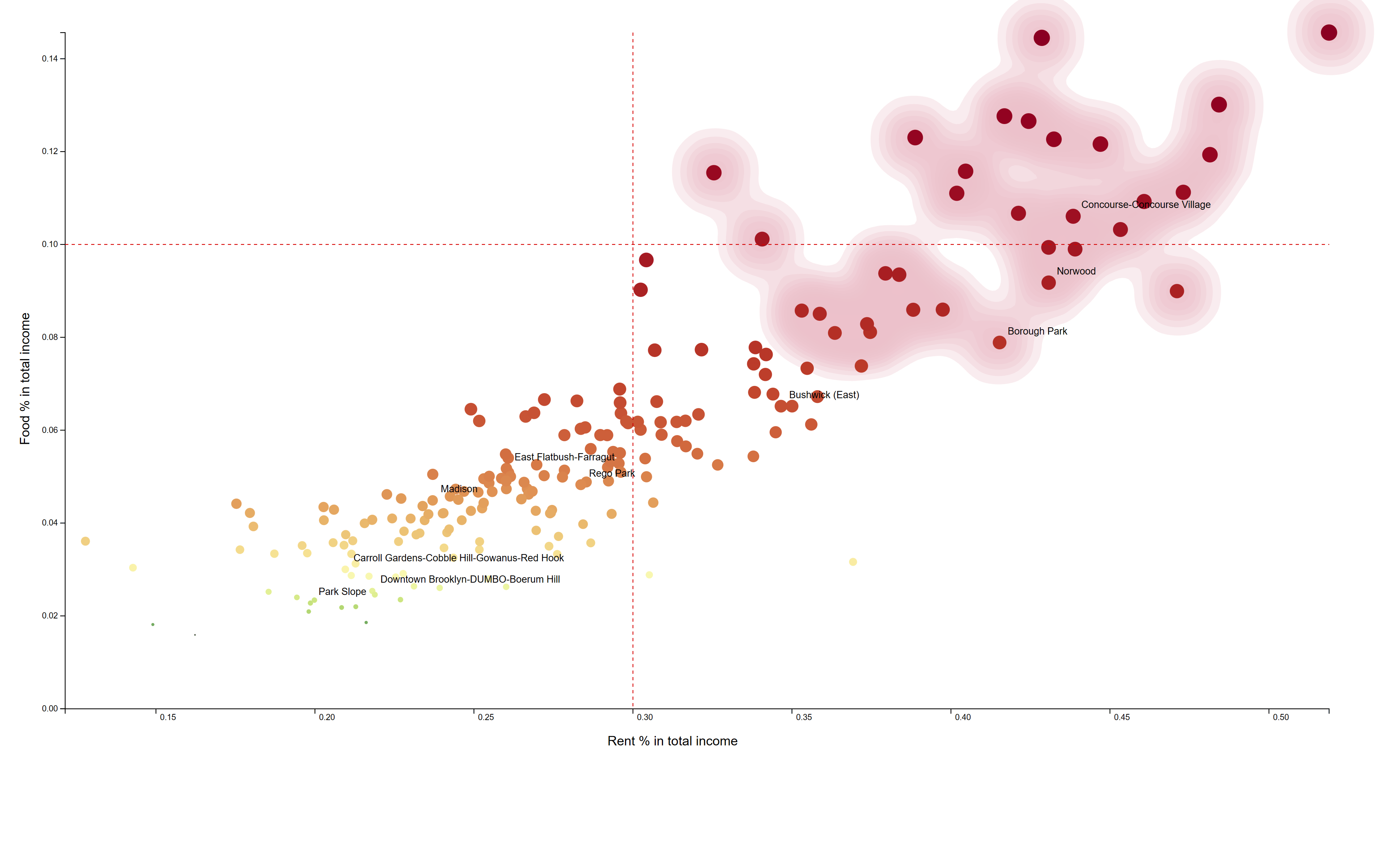

Investigation I: Deeper Financial Burdens

Though the 33,714 USD cutoff for affording healthy meals is a good indicator for understanding neighborhoods with financial difficulties, it could also be justified with another financial parameter-- rent. According to many major financial institutions, such as SoFi and Chase, it is recommended that families should invest less than 30% of their income towards rent/mortgage in order to be financially sound.

In this particular graph, there is a comparison between the %of income that goes towards food, and the %of income that goes towards rent, with the dashed red lines representing the recommended financial cutoffs. Neighborhoodsthat exceed both of these cutoffs are prime candidates that are more vulnerable to food insecurity. In this case, these neighborhoods get a distinction gives them more priority when it comes to classifying which neighborhoods suffer from food insecurity the most.

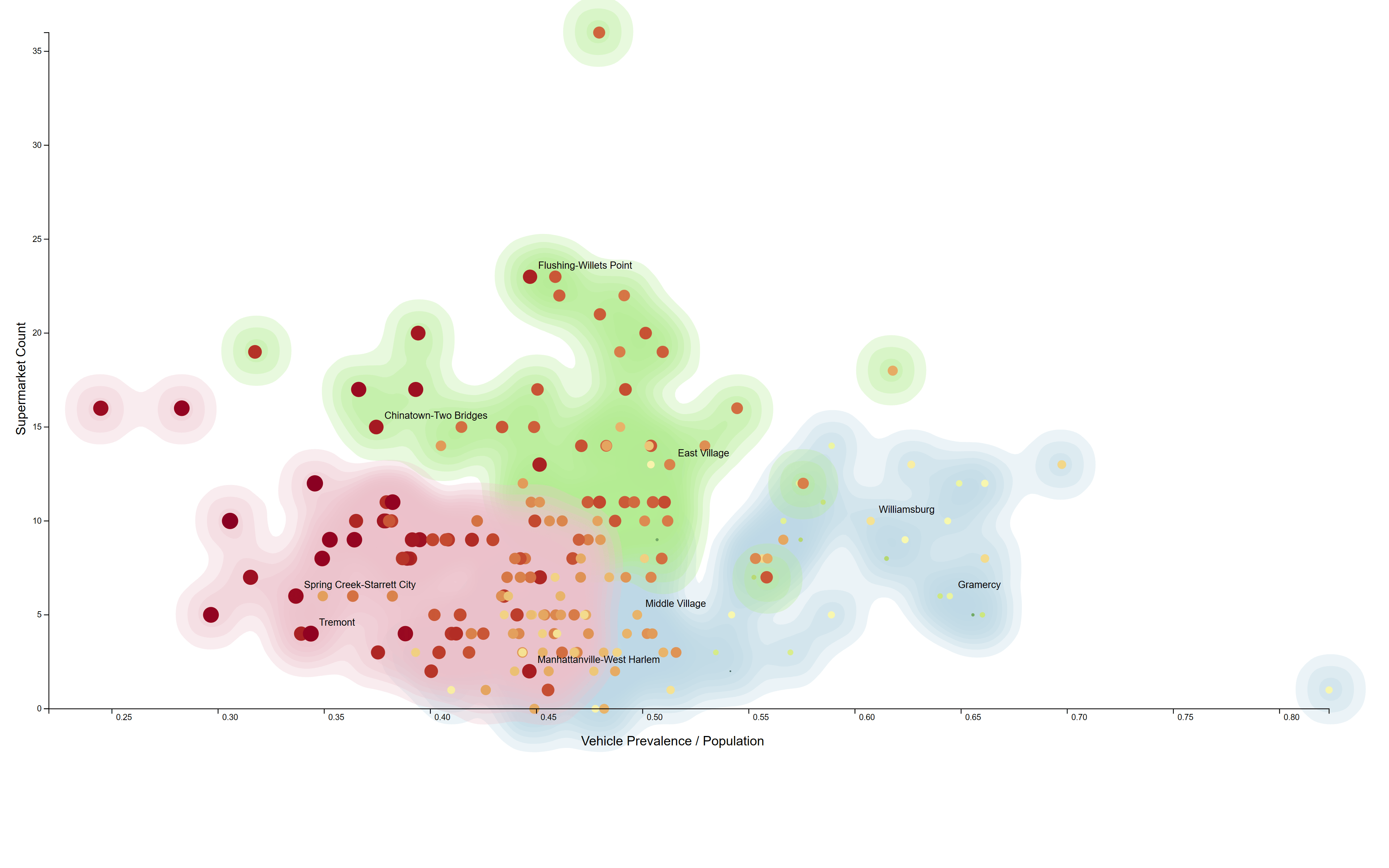

Investigation II: Vehicle Prevalence

In certain areas, especially in the outskirts of New York City, neighborhoods tend to become more sparsely populated, with infrastructure being more spread out. In these investigations, these can mistakenly read as places that may have more difficulty with accessing adequate nutritious infrastructure.

The graph is divided into three groups: one where there are lower amounts of supermarkets but compensated with higher vehicle ownership (blue), one where there are less vehicles but enough supermarkets accessible to the public (green), and most importantly, one where there are inadequate amounts of vehicle ownership and supermarket infrastructure. This ultimately filters out any false positives regarding any neighborhoods that may be seen as food insecure due to their sparsely populated food infrastructure.

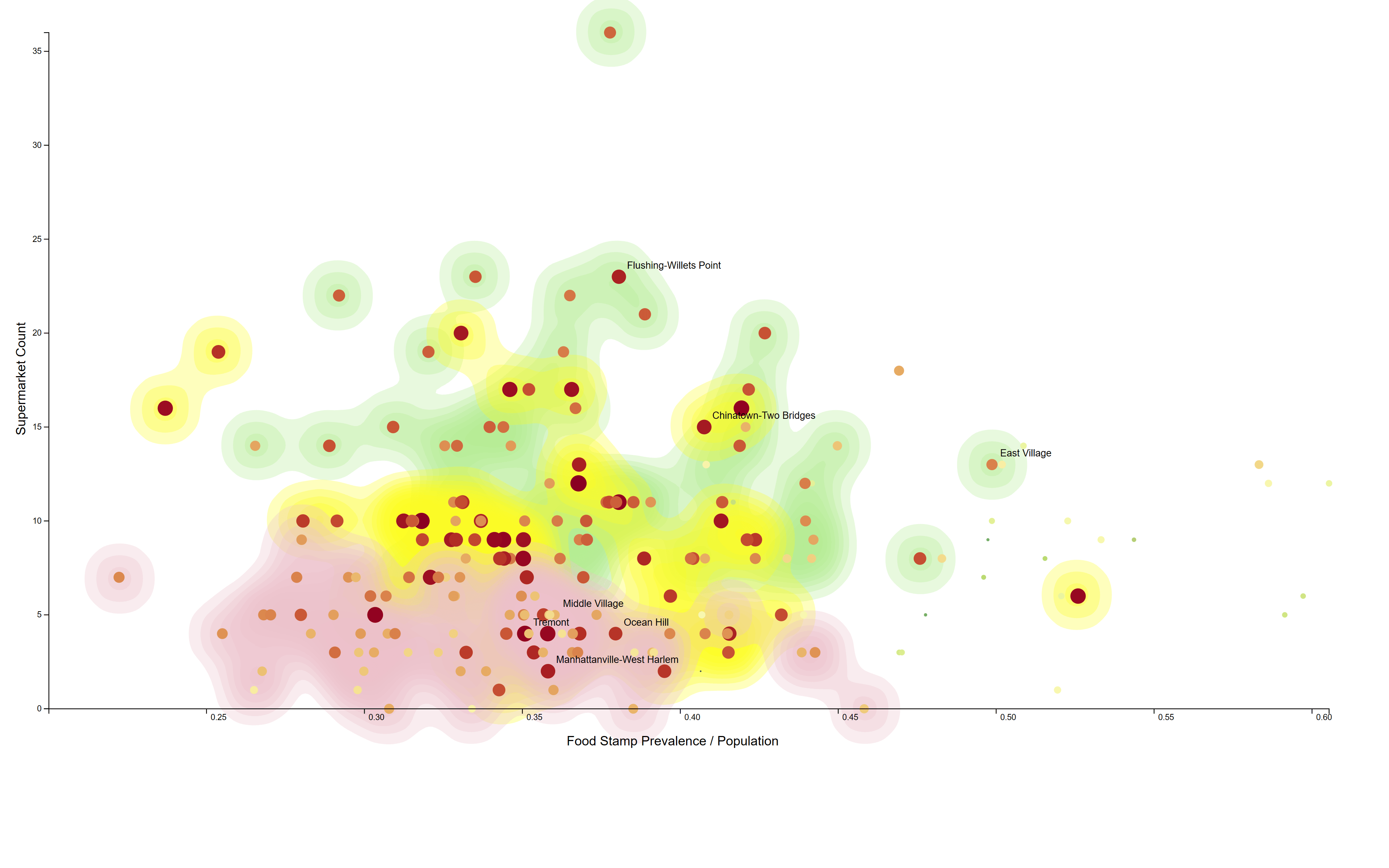

Investigation III: Food Stamp Prevalence

Food stamps are typically given to individuals that need assistance with obtaining food. In this study, food stamp prevalence (Source: US Census 2020 ACS5) is correlated with supermarket counts, and income. This scatterplot also divides into three groups, those with good access to supermarkets and are able to afford it (green, i.e. Sunset Park), those with decent access to supermarkets but have meager means of purchasing goods (yellow, i.e. Central Harlem), and those who have neither the means of supermarket access and/or have higher prevalence of food stamp assistance (red, i.e. Ocean Hill).

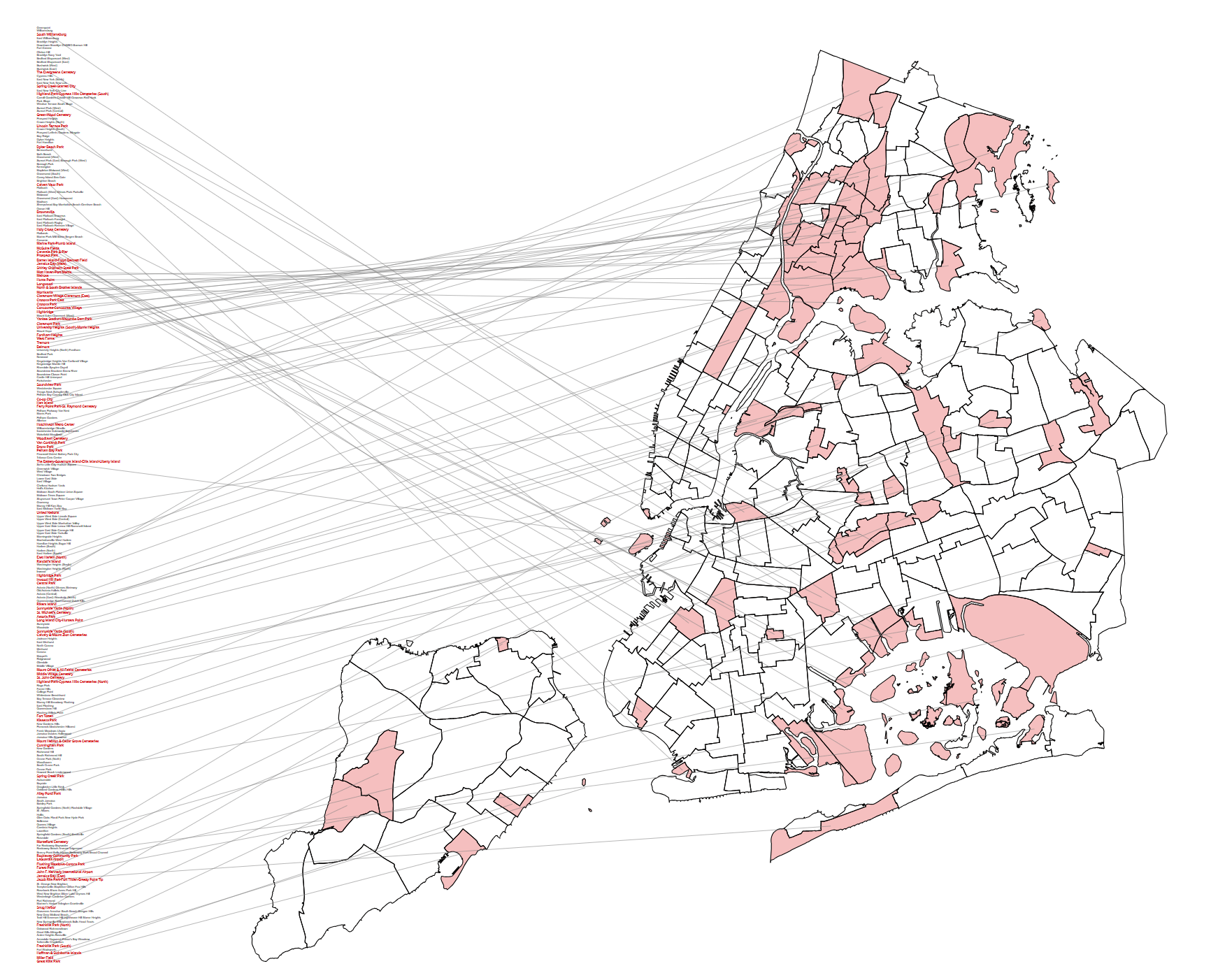

Where is it?

Based on these results, neighborhoods are either classified as a food desert (pink), food swamp (yellow), or food oasis (greens). From these results, one oasis, swamp and desert will be chosen and investigated.

What Does Food Insecurity Look Like?

Ideally, neighborhoods should have infrastructure that allows for adequeate access to healthy food options. However, in the case of places with food insecurity, there are holes in the infrastructure that give food insecure places their classification.

Within this investigation, a food oasis is used as a control group and is compared to other food insecure neighborhoods in order to show the qualitative differences and contrasts between infrastructure.

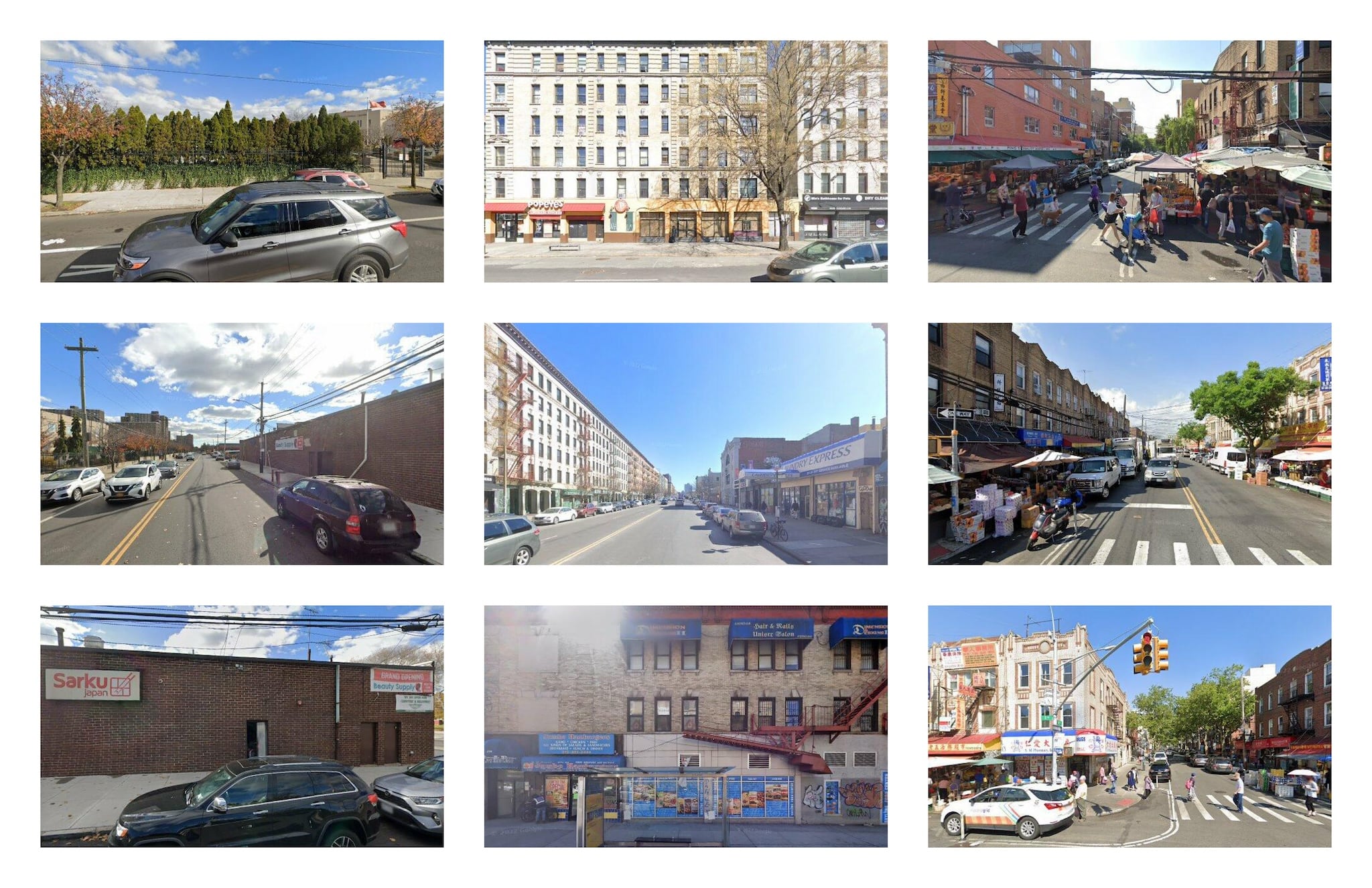

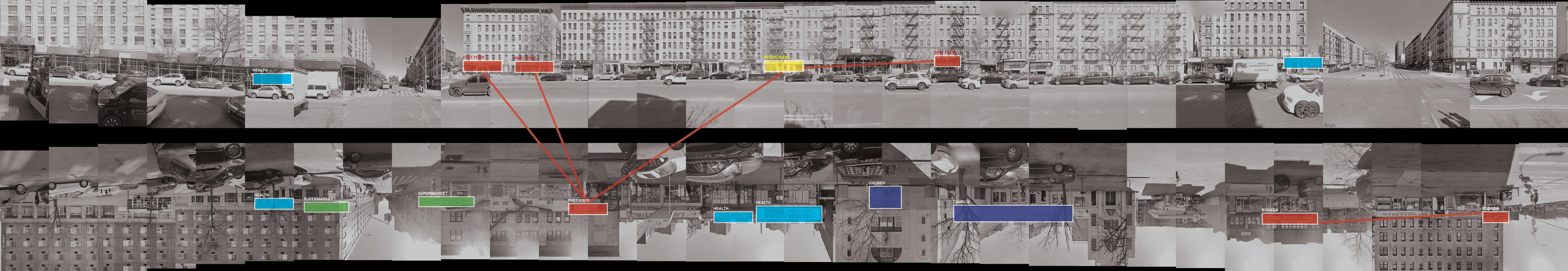

Using google street imagery, a rough panorama is stitched together. All these captures are taken every 10 meters, and all represent the same distance.

Food Oasis: Sunset Park 8th Avenue, 54th-57th Street.

There is an abundant and dense network of grocery vendors, along with a fair share of dining options. Though this is a fairly low income neighborhood, the availability of resources and the low dependency on food stamps indicates a neighborhood with sufficient access to healthy options.

Food Desert: Starrett City. Louisiana Avenue and Twin Pines Drive

Starrett City finds itself to only have two total supermarkets located in strip malls, surrounded by various fast-food options. The high prevalence of fast-food establishments suggests the neighborhood could populate with more infrastructure that is not just concentrated within the two strip malls in the center of the neighborhood.

Food Swamp: Central Harlem-North. 145th Street, Bradhurst Avenue to Adam C. Powell Boulevard

Compared to the Sunset Park example, CH-N has a lower density of food infrastructure. However, fast food & convenience options are more plentiful compared to the supermarkets available. However, it is interesting to note the amount of health infrastructure around. Is this due to the higher prevalence of health problems? This implies that though there are options available for healthy dining, the combination of the high food stamp prevalence in this neighborhood hints at the preference of more affordable options

What's on the Menu?

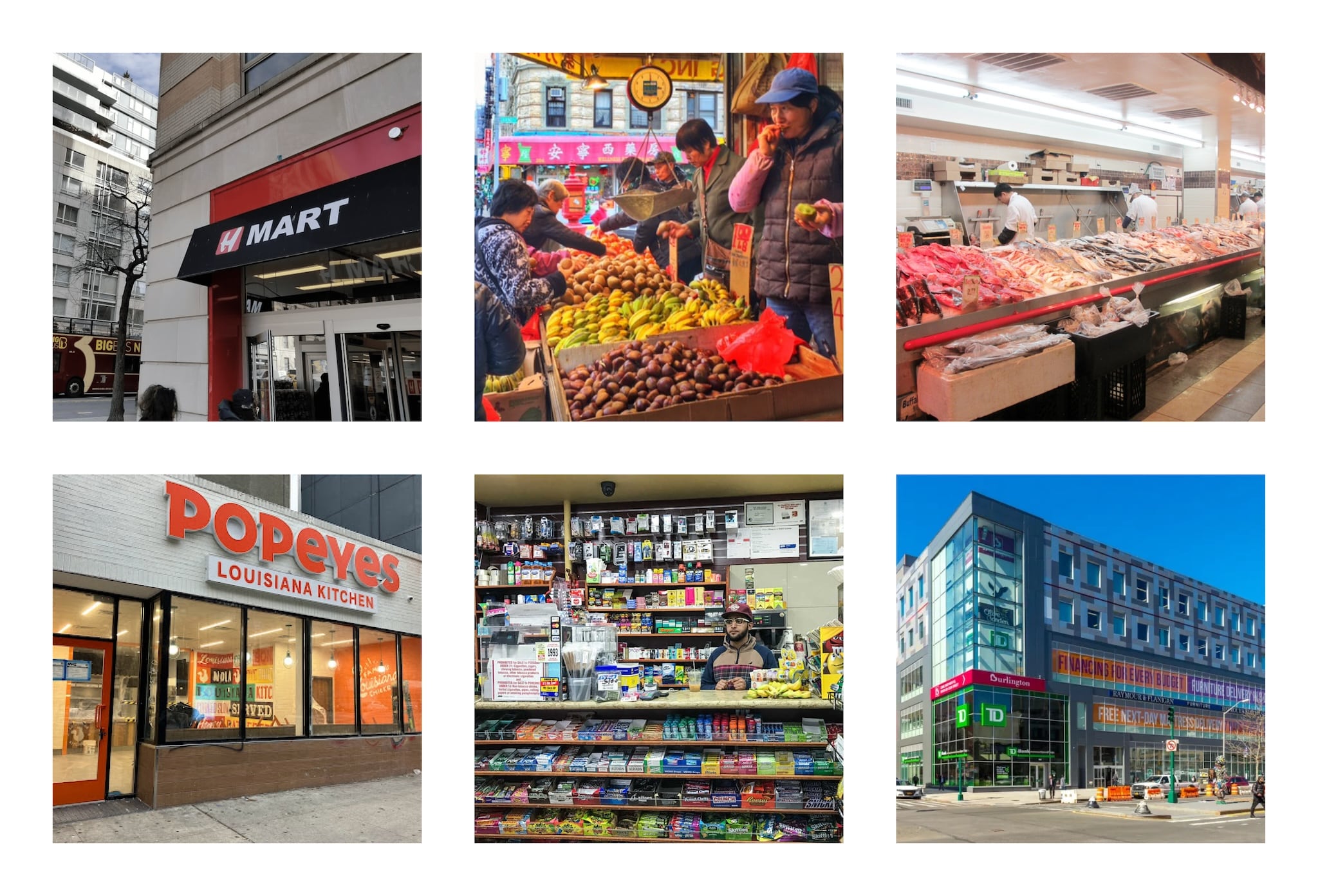

FOOD DESERT: Starrett City

When it comes to the food infrastructure of Starrett City, there are only two supermarkets in the entire neighborhood. Outside of these supermarkets, the food options mostly involve fast food, dominated by chain establishments (i.e. Dunkin, Sarku Japan, etc.) that take up Starrett City's retail spaces. With 52% of the neighborhood having food stamps, it is also evident that healthier options are more difficult to obtain.

Starrett City's infrastructure is mostly apartment complexes, with two strip malls. The strip malls also have vast amounts of parking space too, which is ironic considering the general lack of automobile vehicle usage in comparison to other neighborhoods.

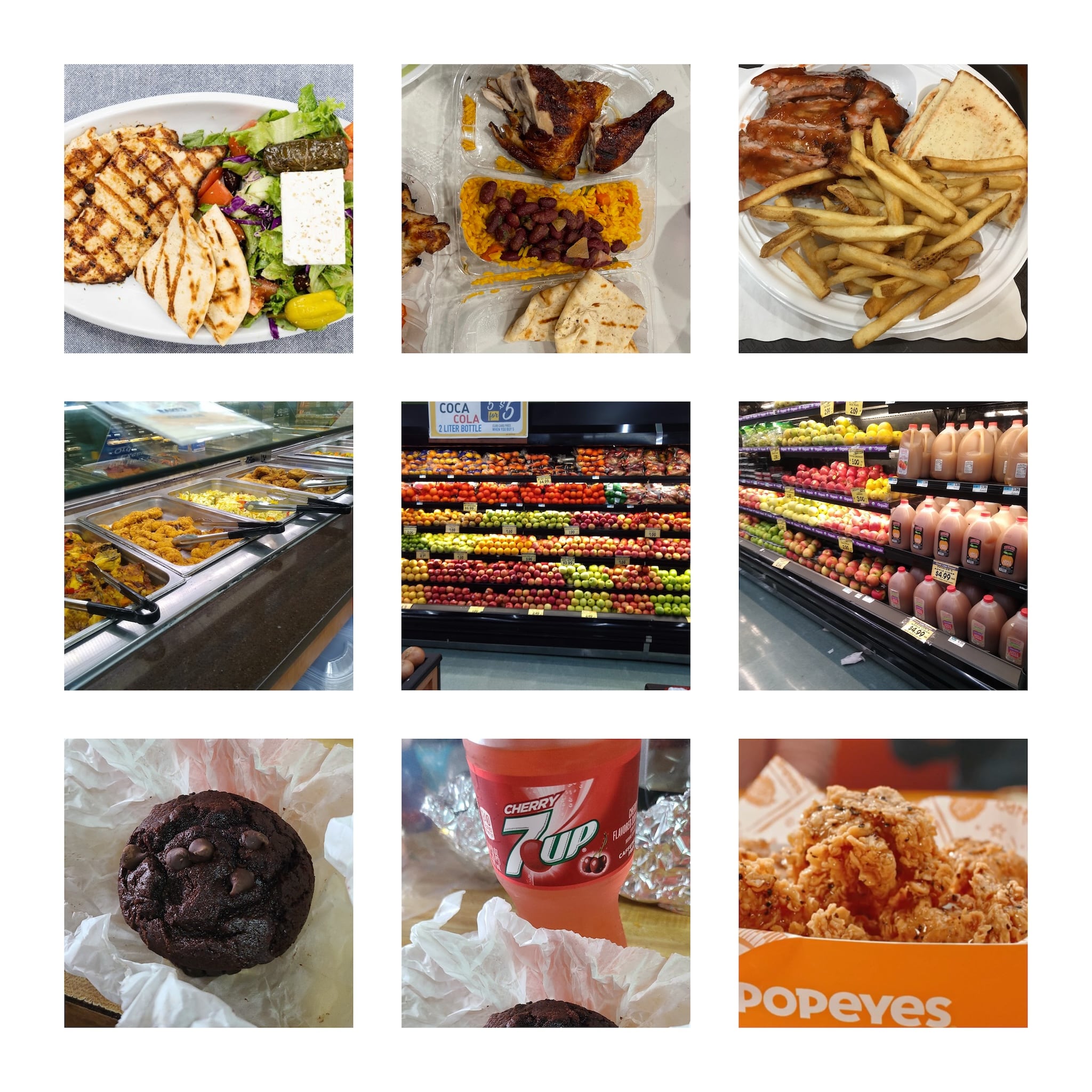

FOOD SWAMP: Central Harlem-North

CH-N differentiates itself from the food desert example by having denser infrastructure-- especially with a greater amount of supermarkets overall, unlike Starrett City which only has two. However, the presence of fast-food options is similar to its food desert counterpart is prevalent-- bodegas and fast food choices still outnumber supermarket infrastructure. With around 45% of their populace also using food stamps, it is clear that financial assistance is needed to access healthier options.

CH-N has much more variety when it comes to infrastructure, unlike Starrett City which is mainly composed of High Rise buildings, strip malls and asphalt lots. The density of their infrastructure also makes the lack of vehicles not as much of a problem, as this offset by plentiful access to the MTA Subway and Bus lines.

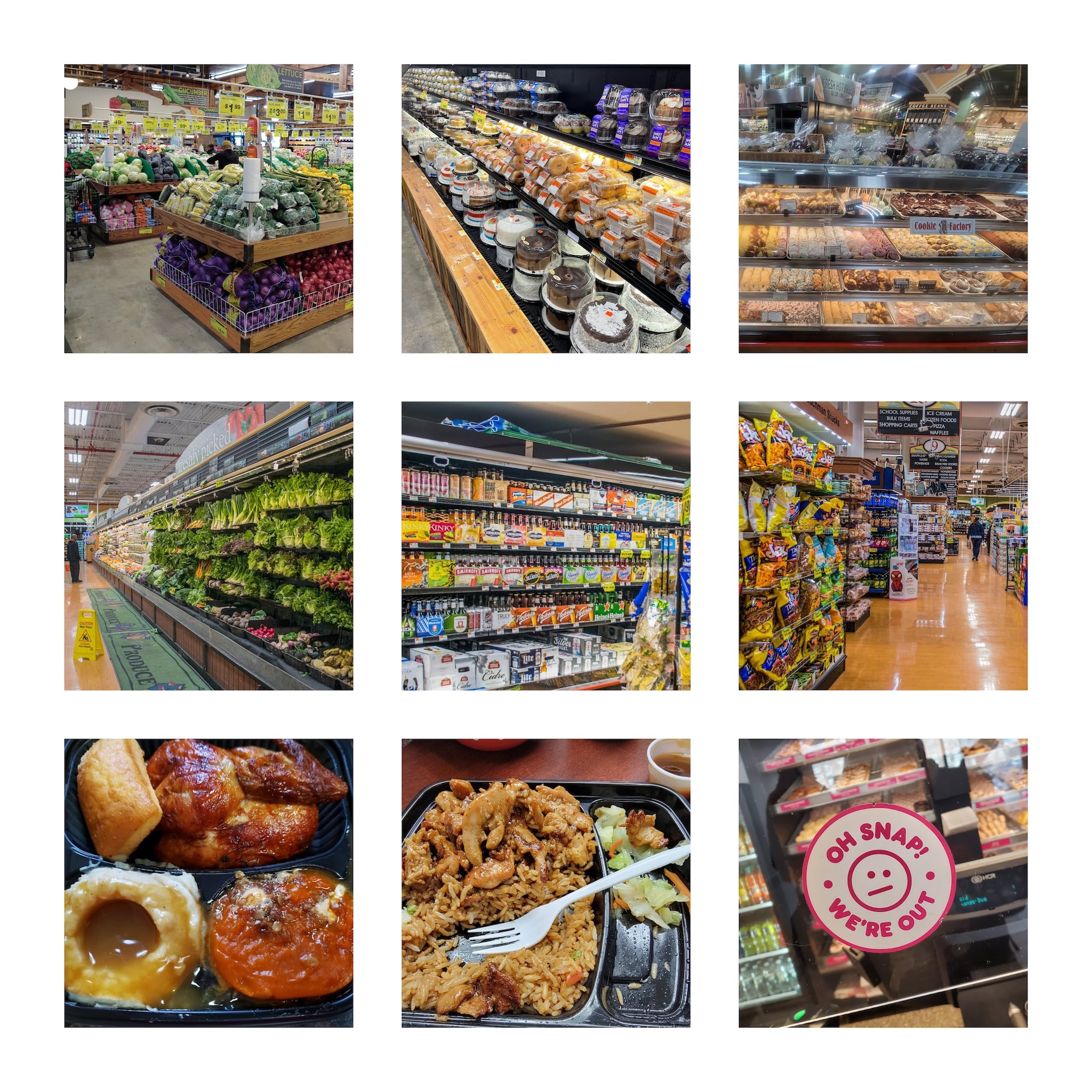

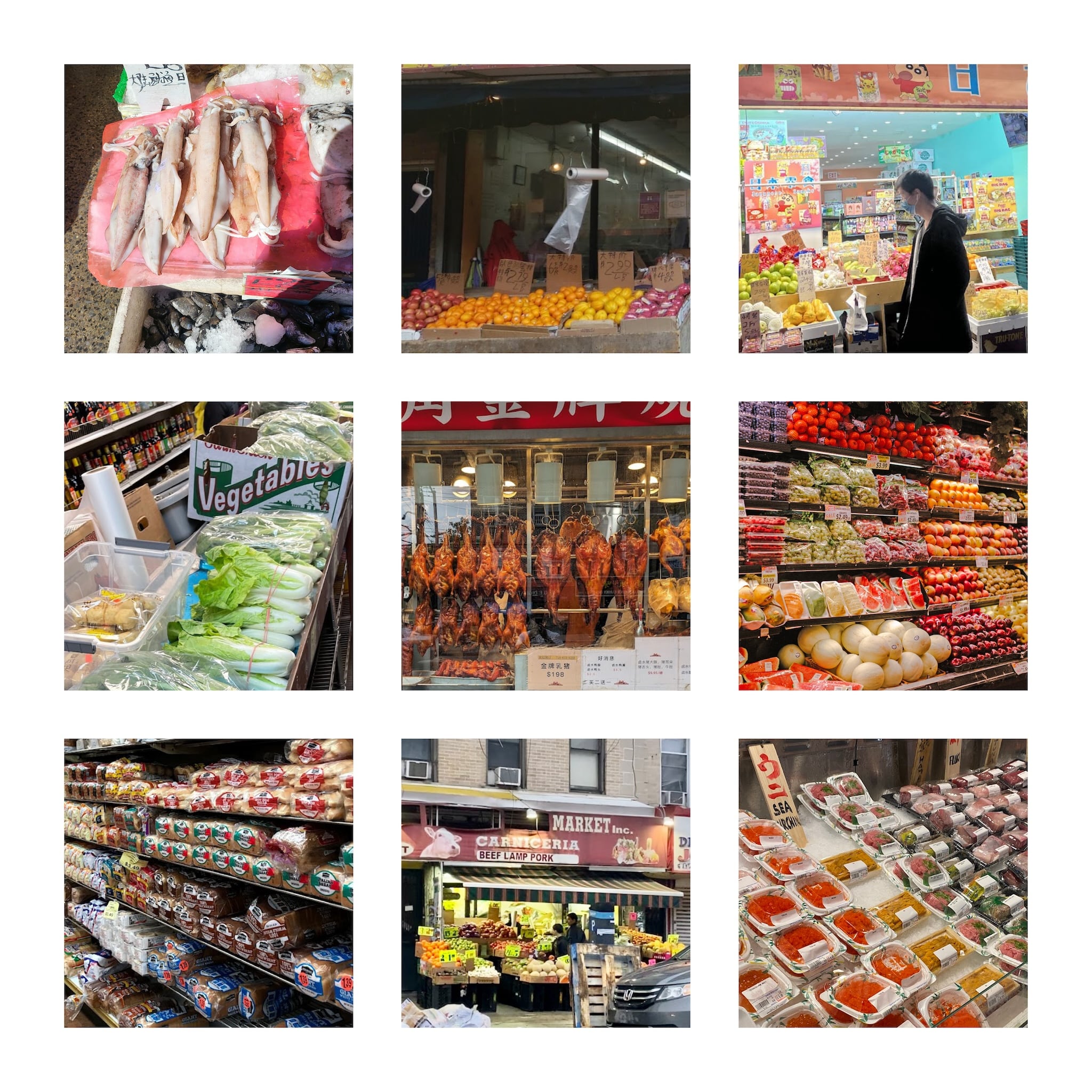

FOOD OASIS: Sunset Park

Sunset Park differentiates itself from its food insecure counterparts by offering a dense supermarket network, with almost every block having a food vendor. Unlike supermarkets in Starrett City or Central Harlem- North, Sunset Park proudly displays their produce outside of their premises, and even allot smaller venues to have fresh produce, which would've otherwise read as fast food restaurants or cornerstores in the food-insecure neighborhoods.

With only 28% of residents using food stamps, and having median incomes similar to Central Harlem-North, along with similar building typologies, Sunset Park sets a good example of how lower-income neighborhoods can still have ample access to healthier options at an affordable price. Ultimately, Sunset Park minimizes the presence of fast food restaurants, in favor of local vendors.

Conclusion

Food insecurity affects many neighborhoods in New York in different ways, whether it’s through lack of healthy infrastructure, or the inability to afford healthy options. Though there are many incumbent programs managing the food insecurity issue in the city, most of them reach out to a smaller clientele in order to maintain the quality of their outreach. Trying to create a one-size-fits-all solution that could encompass the whole city would not only be extremely expensive, but would also be unsustainable to properly feed a food-insecure population of over 200,000 individuals.

Within these neighborhood-scale studies, it is essential to note that their respective infrastructures and populace are different. There can be cases where food insecurity takes the form of an area with an abundance of fast-food establishments and a lack of supermarket access. There can also be cases where food insecurity comes from a sparsely populated area with a majority senior-citizen demographic that have a harder time taking the trip to their local vendors. The simulations above show how it is important not to look at just one solution, but rather to mix and match different solutions that tailor the demographics and resources these neighborhoods have.

Ultimately, Biting the Big Apple is a stern message to NYC’s government: it has the responsibility of allocating these programs depending on what makes the most sense for these particular neighborhoods. This process is only a start, as it uses existing infrastructure– long term, the City has to implement permanent foundations in order to maintain the healing process these introductory interventions offer.