Unpacking the Made_Mycelium Acoustic Module

Julia Kwon

Introduction

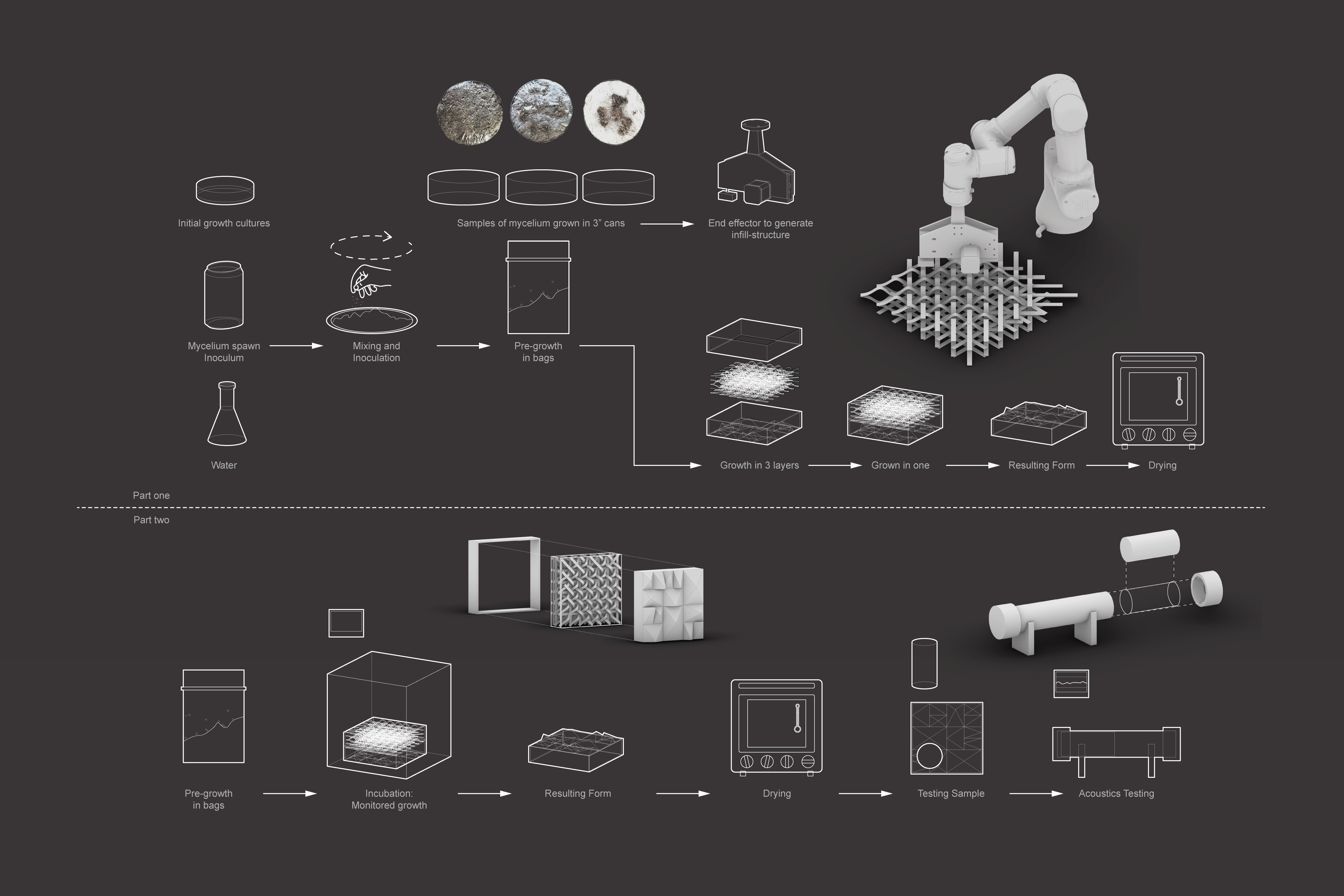

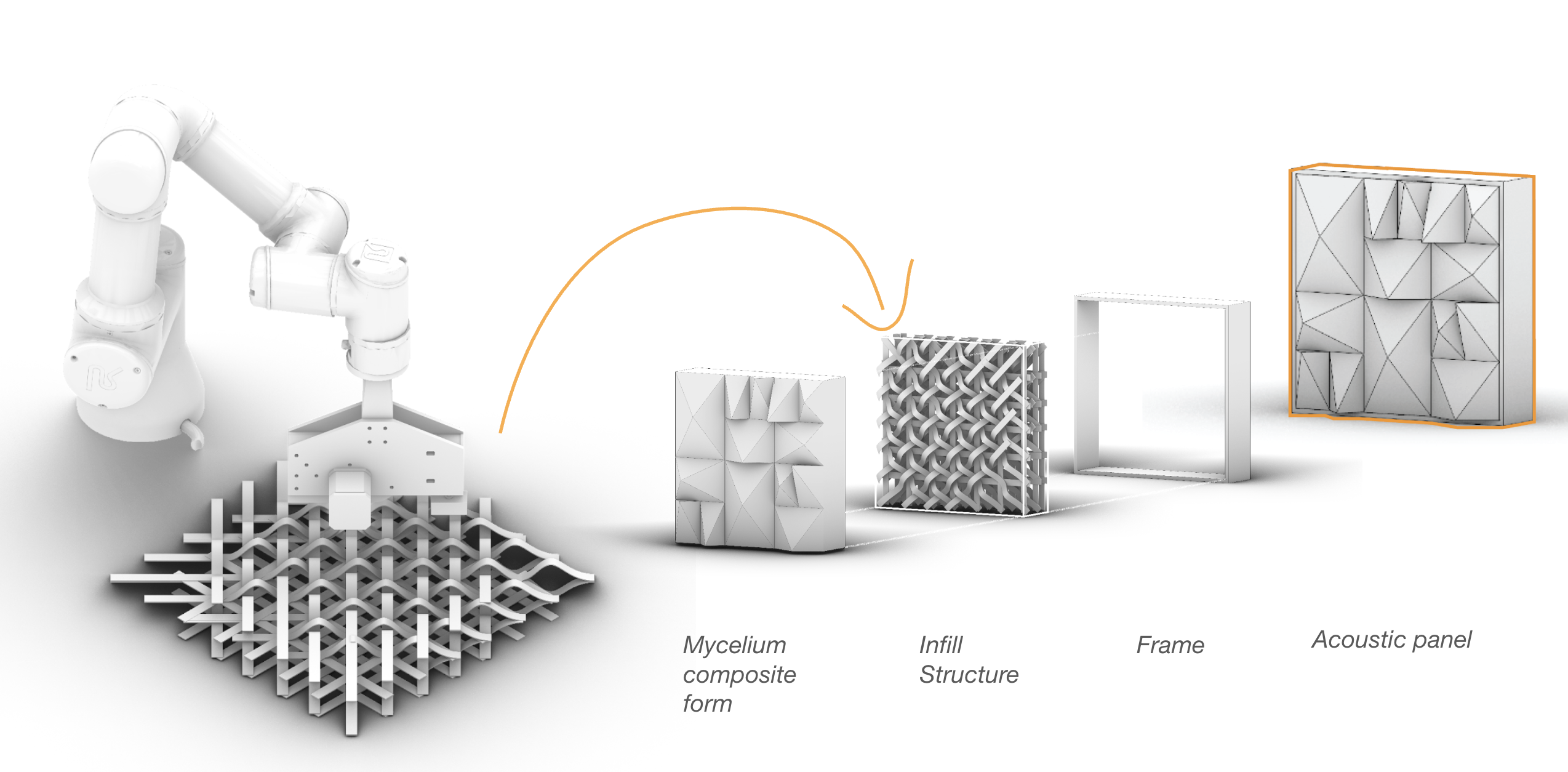

This document serves as a breakdown of the thoughts, processes, and methodologies that shaped this capstone project. It outlines each phase of development—from digital fabrication involving a robotic arm, to monitoring the biological growth of the prototype, and testing its acoustic performance—offering a comprehensive view of both technical execution and conceptual grounding.

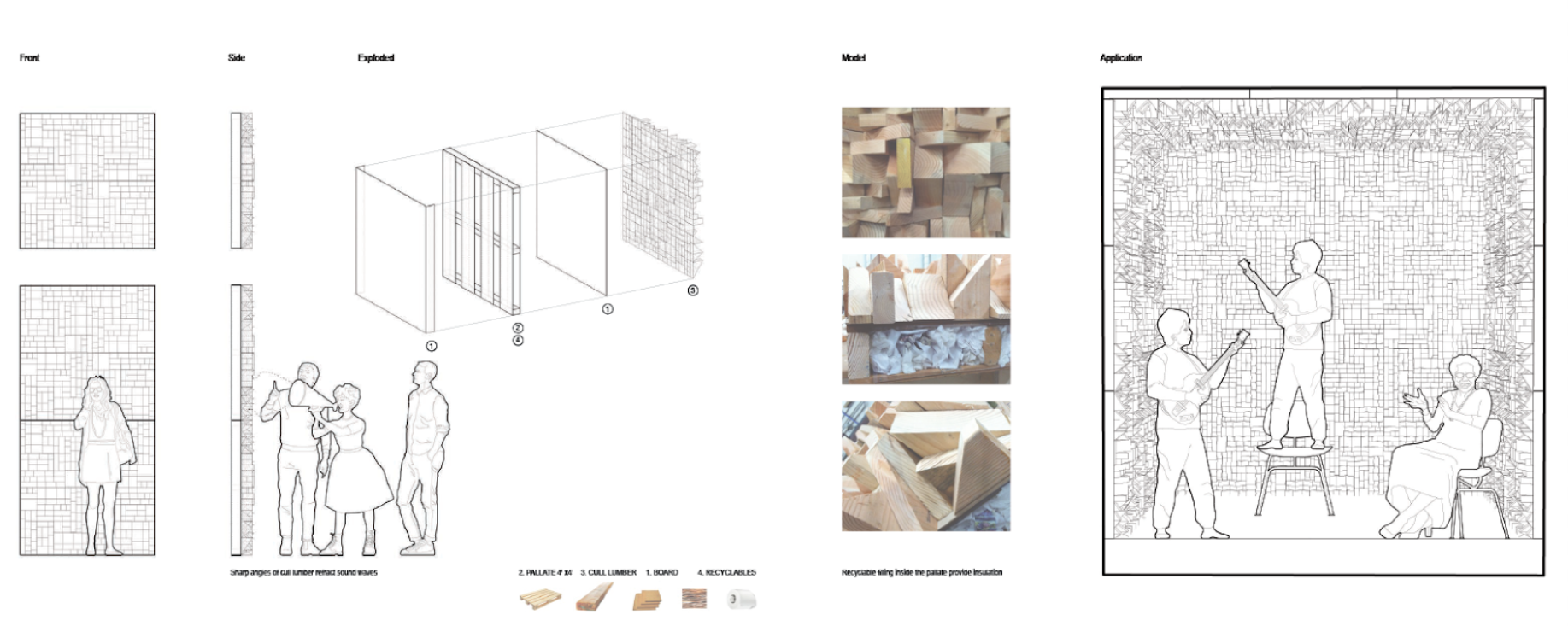

At the core of this investigation is an ongoing interest in comfort and privacy as essential conditions within the built environment. This interest led to the design and construction of a modular acoustic panel. In a previous iteration, I used cull lumber, shipping pallets, and recycled paper to create a sound diffuser.

The current project marks a shift from working with resource-depleting materials to exploring regenerative, bio-based alternatives through the cultivation and prototyping of mycelium.

What Is This About?

This project prototypes a modular acoustic panel grown from mycelium, combining fabrication, cultivation, and performance testing. It aims to demonstrate the material’s viability by validating each stage—from biological growth to acoustic effectiveness.

Where Does the Research Place Mycelium?

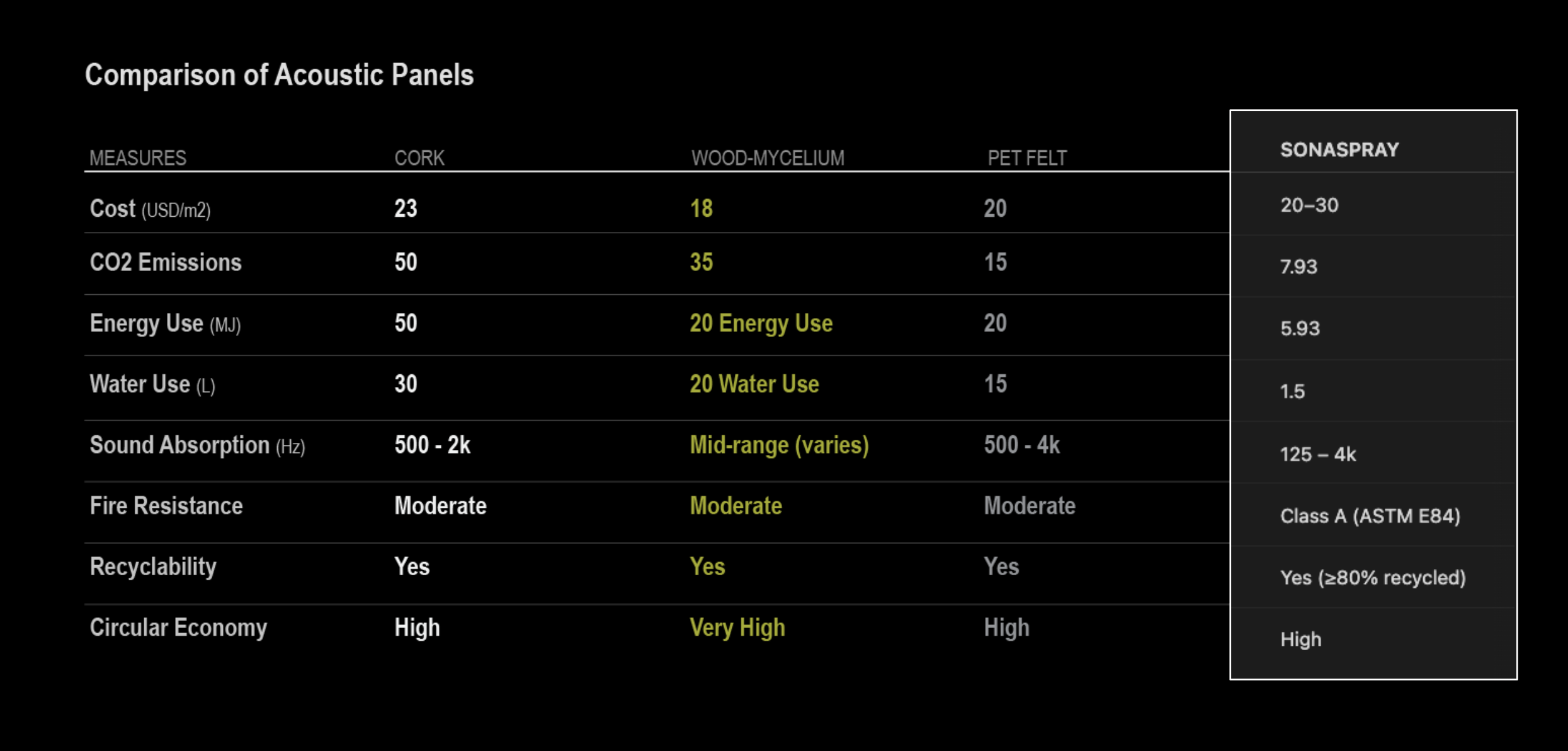

According to synthetic performance data, mycelium composite panels rank consistently in the middle tier across several key measures—striking a balance between environmental responsibility, material circularity, and acoustic performance.

Cost and Environmental Impact

Mycelium exhibits moderate CO₂ emissions (35 kg CO₂ eq), placing it between Cork (50)[1] and PET Felt (15), and significantly outperforming SONASPRAY (793). It also shows relatively low water and energy use, aligned with PET Felt and well below Cork.

Sound Absorption

Mycelium’s absorption is categorized as “mid-range,” varying with substrate density and growth conditions. In contrast, SONASPRAY reports the highest absorption range (125–4000 Hz), as documented in material data sheets from [ICC Evaluation Services for SONASPRAY][2], highlighting its use in large-scale commercial applications.

Fire Resistance and Circularity

Like PET and Cork, Mycelium offers moderate fire resistance, with a notable advantage in circular economy metrics, rated “Very High”—largely due to its glue-free growth and biodegradability, a feature emphasized by researchers at the [Kassel Institute for Sustainability Design][3] in their studies on fungal biomaterials.

Recyclability

All four materials are recyclable, but mycelium’s regenerative lifecycle, as supported by biofabrication research from [SONA][4], aligns closely with circular construction frameworks outlined in their 2024 report on “Bio-Based Acoustic Strategies for Low-Impact Interiors.”

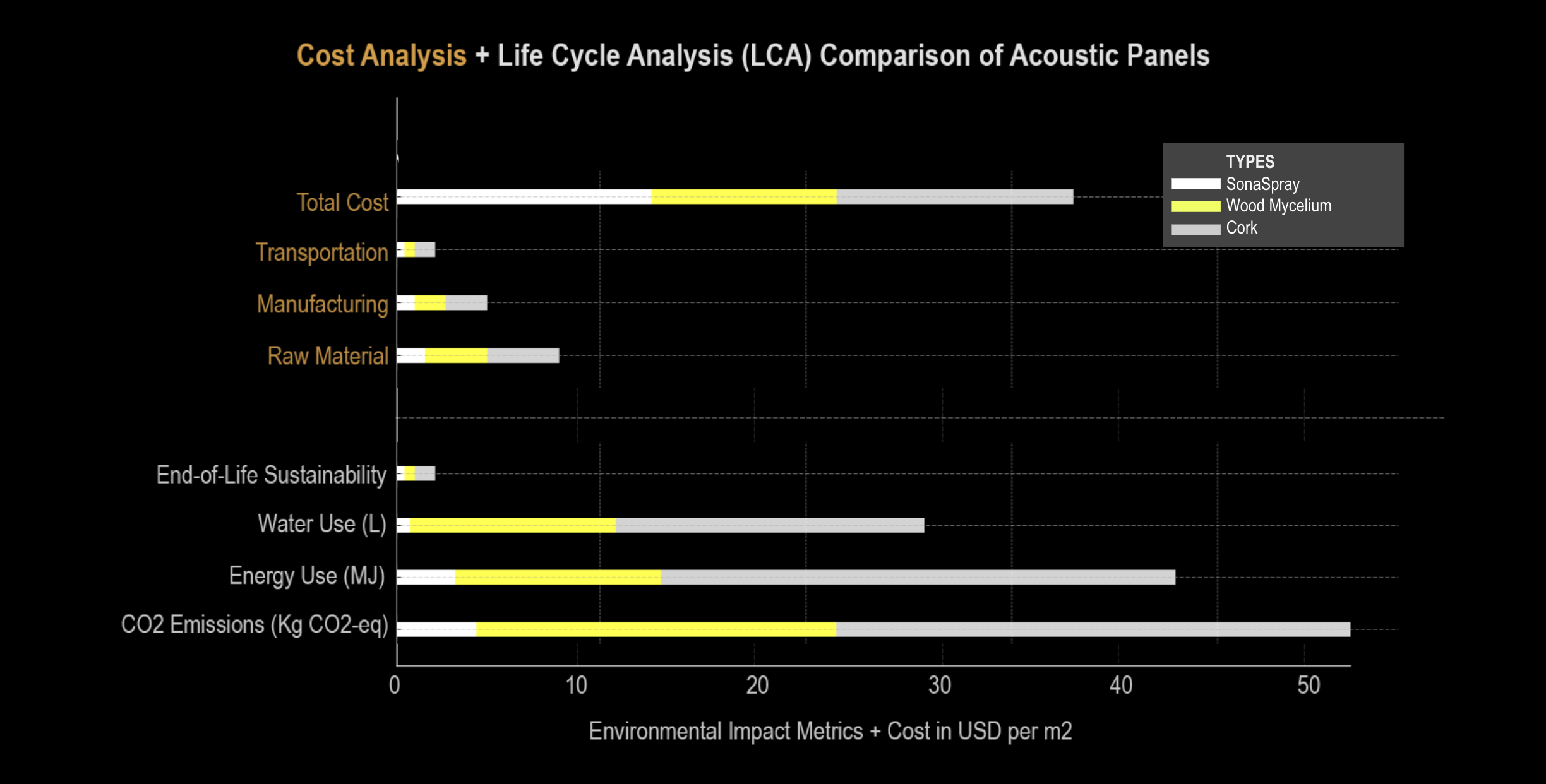

Cost and Life Cycle Positioning

In terms of Cost and Life Cycle Analysis (LCA), wood-mycelium panels remain competitively placed. The second chart below shows that while Cork incurs the highest total cost (approaching $50/m²)[1:1], and SONASPRAY has lower environmental scores but high emissions, Mycelium offers a moderate total cost and balanced environmental footprint, reinforcing its potential as a cost-efficient, low-impact alternative.

This analysis affirms Mycelium’s promise as a viable material for sustainable acoustic construction, particularly for applications where fire performance and ultra-high absorption are not the primary requirement, but decarbonization and reuse are.

How Does It Work?

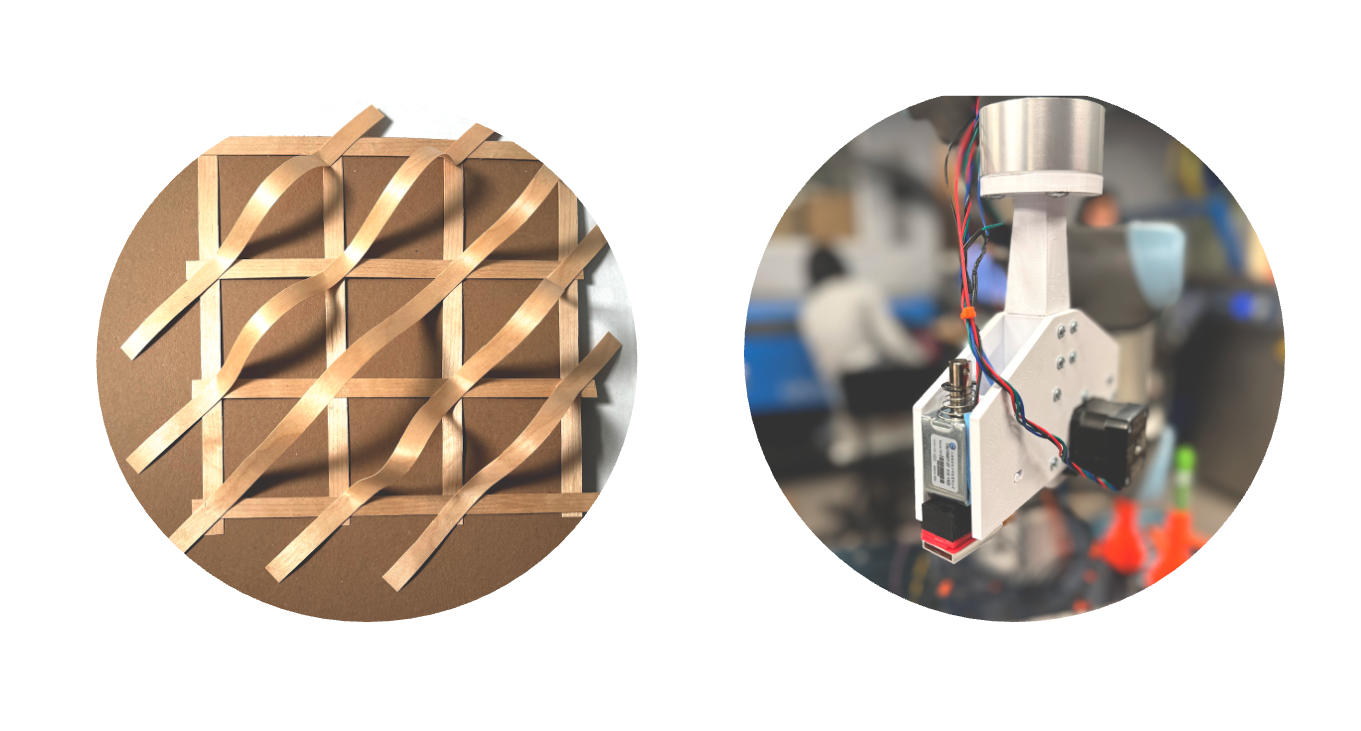

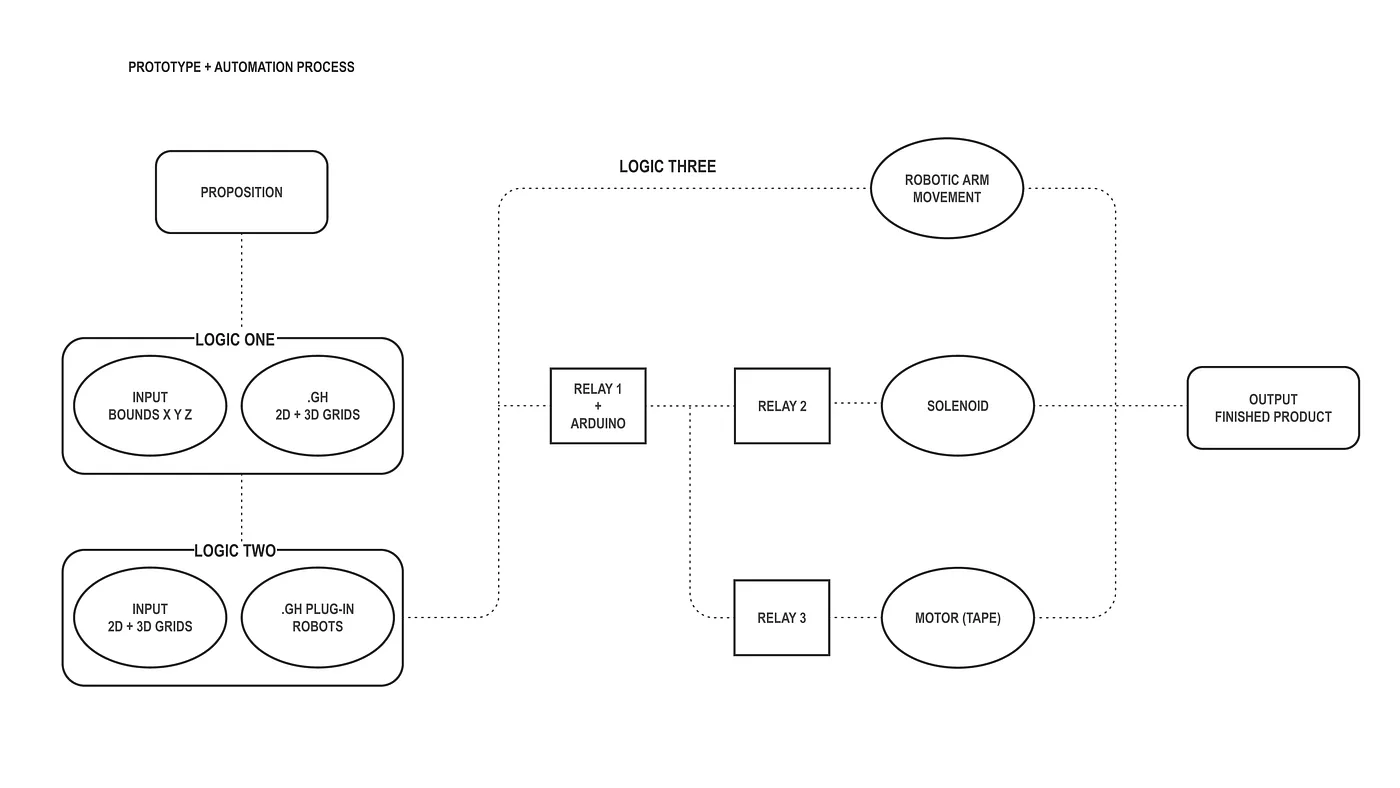

ONE: Making the Set-up

Generating an infill structure using an automation tool comprising two layers, building an end effector (an attachment for the UR3 robotic arm), and using physical computing to integrate all commands and enable the automated digital fabrication process. This approach was undertaken, in part, to explore the potentials of material usage, including its adaptability, malleability, and the application of automation for prototyping.

The development of three sets of scripts was carried out as studies to examine the capabilities of automation tools, with the aim of enhancing efficiency, precision, and creative flexibility in the design and fabrication processes. The development of this tool remains ongoing, with more augmentative processes yet to be investigated to enhance its applications and functionality.

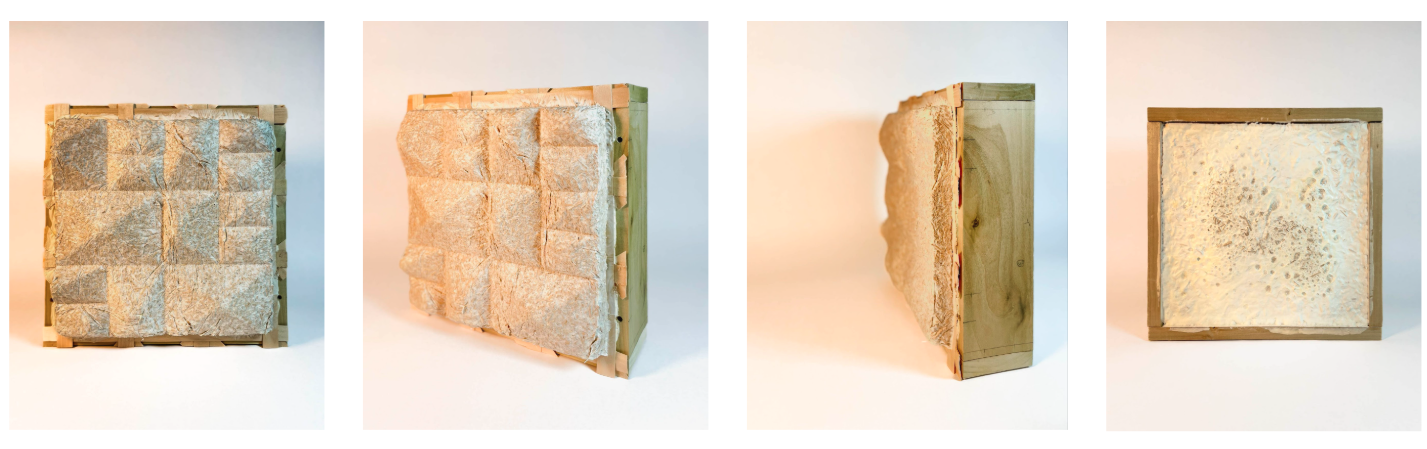

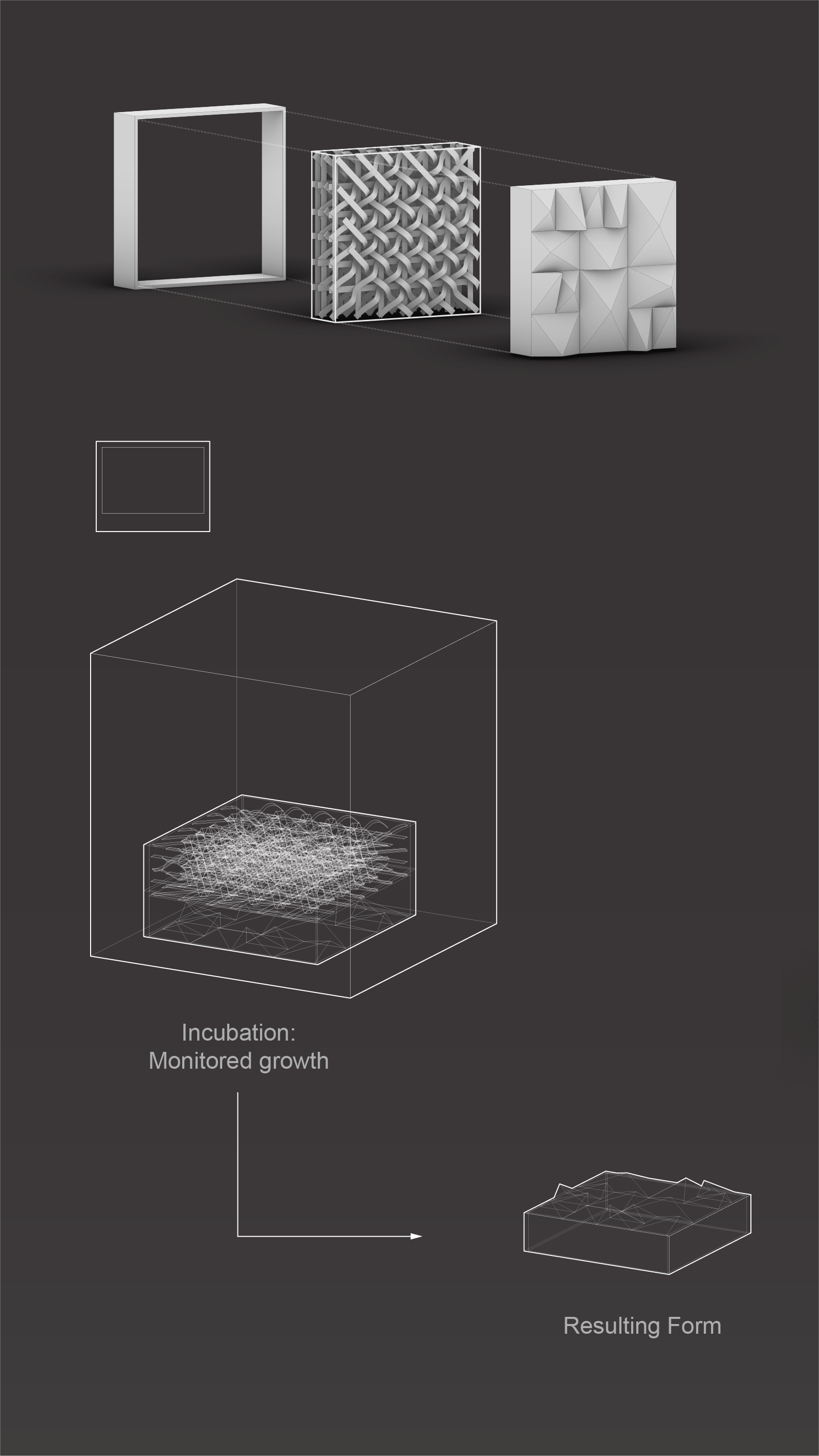

Designing and building the formwork: using simple, triangulated geometric patterns to design and CNC-route the shape. The formwork is built at 3.5 inches in thickness within a 12 x 12 inches frame, providing the structure for the mycelium substrate to sit and grow in.

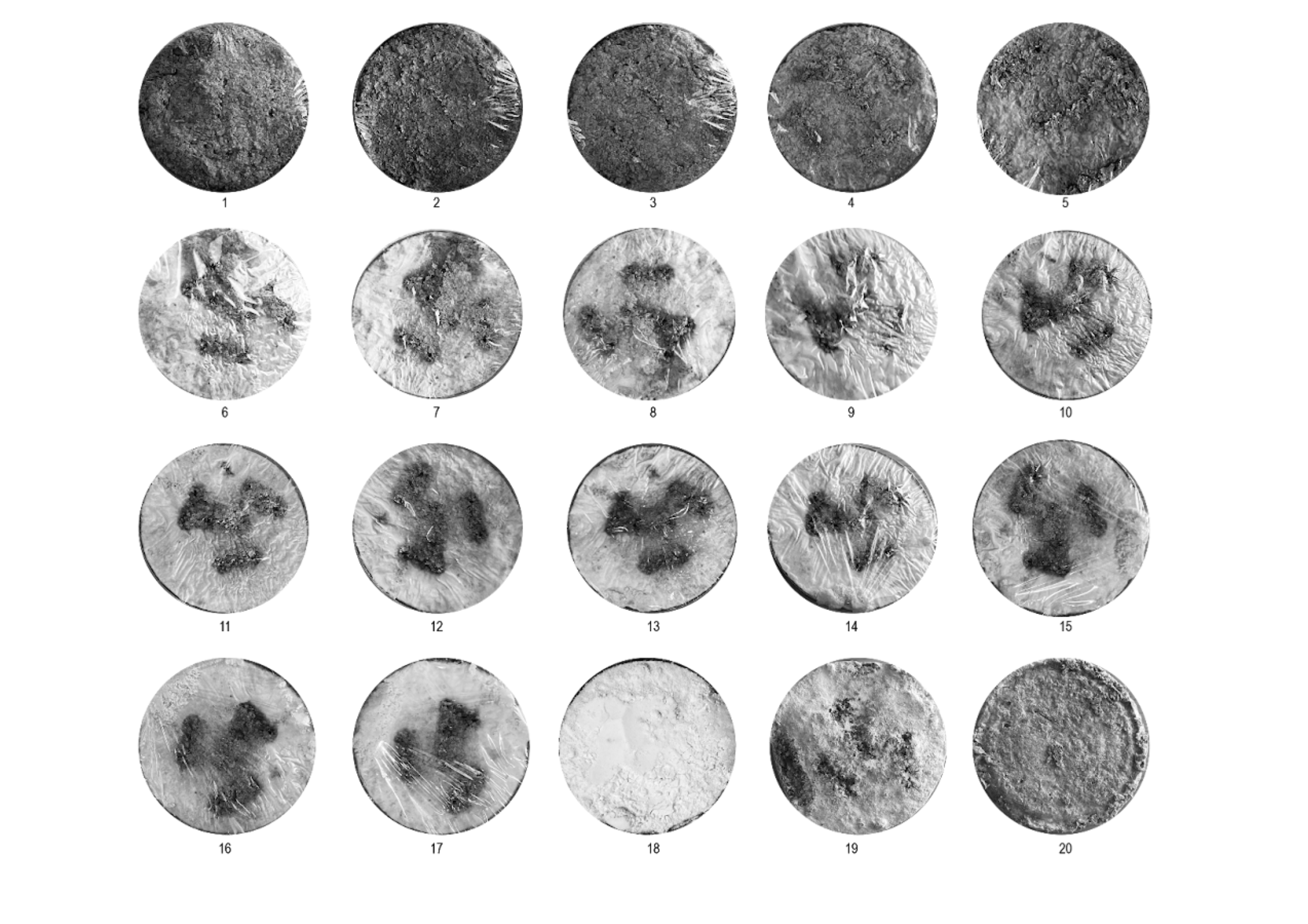

TWO: Growing While Monitoring

A 2 x 2 x 3 feet incubator was purchased for this purpose.

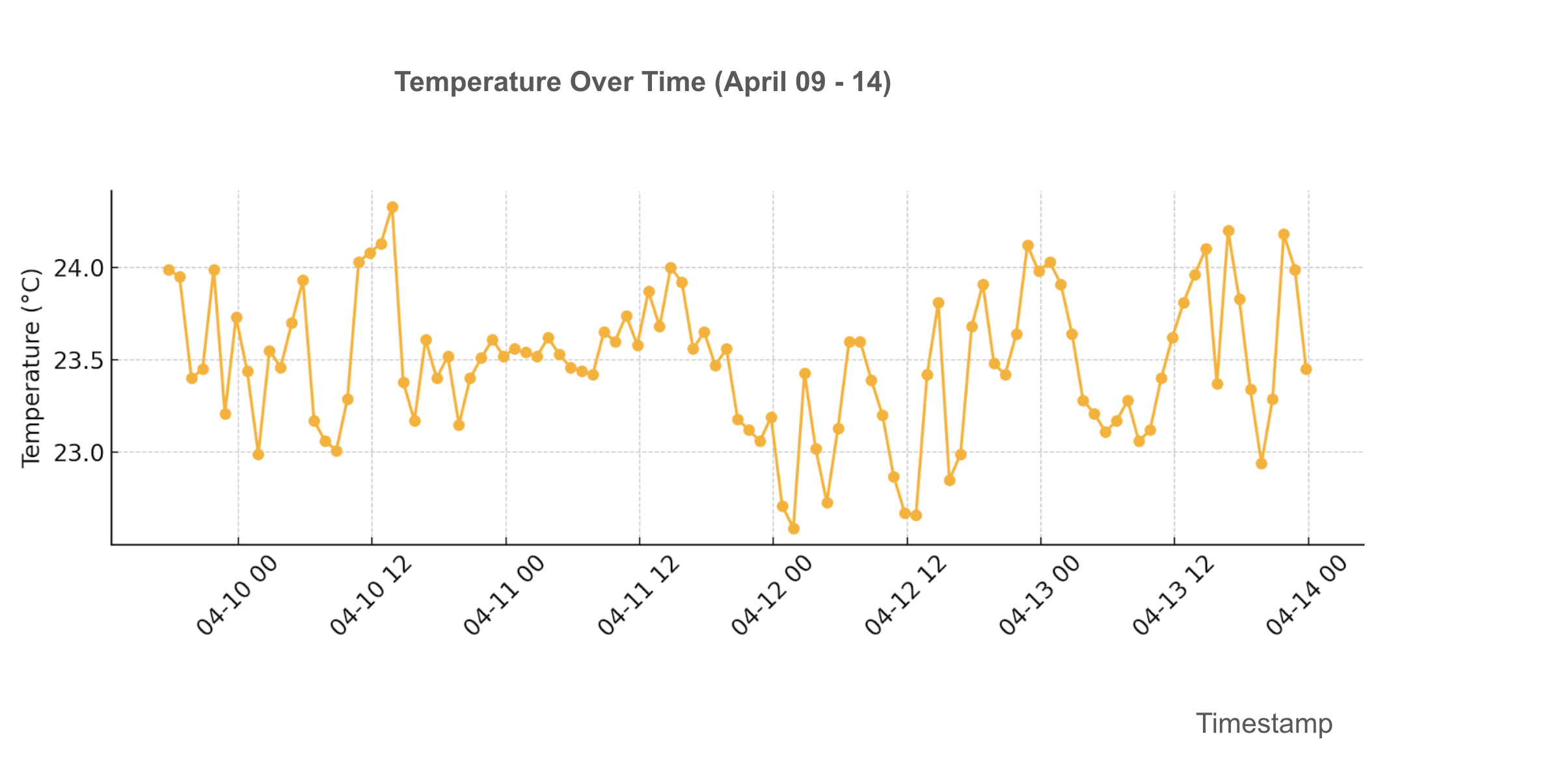

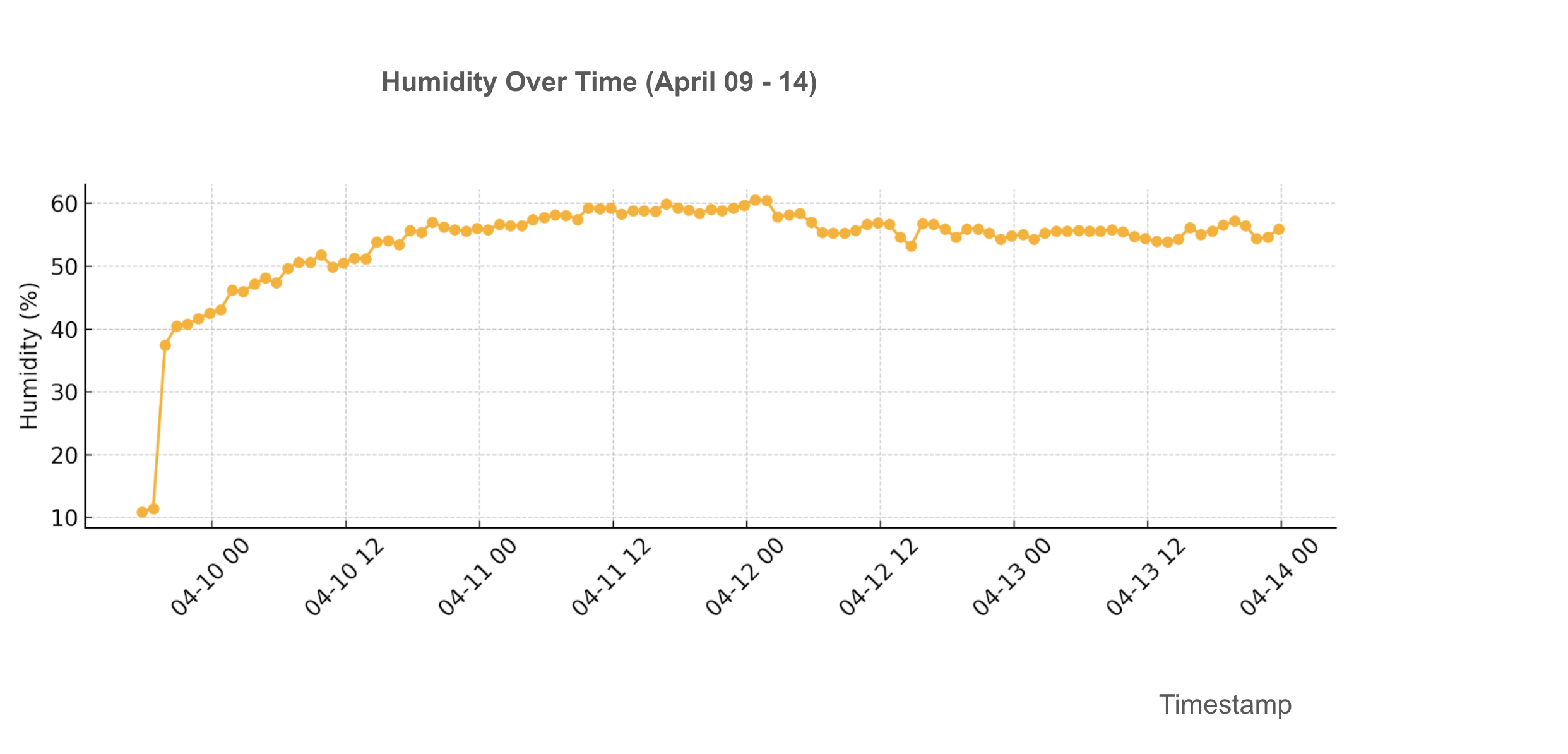

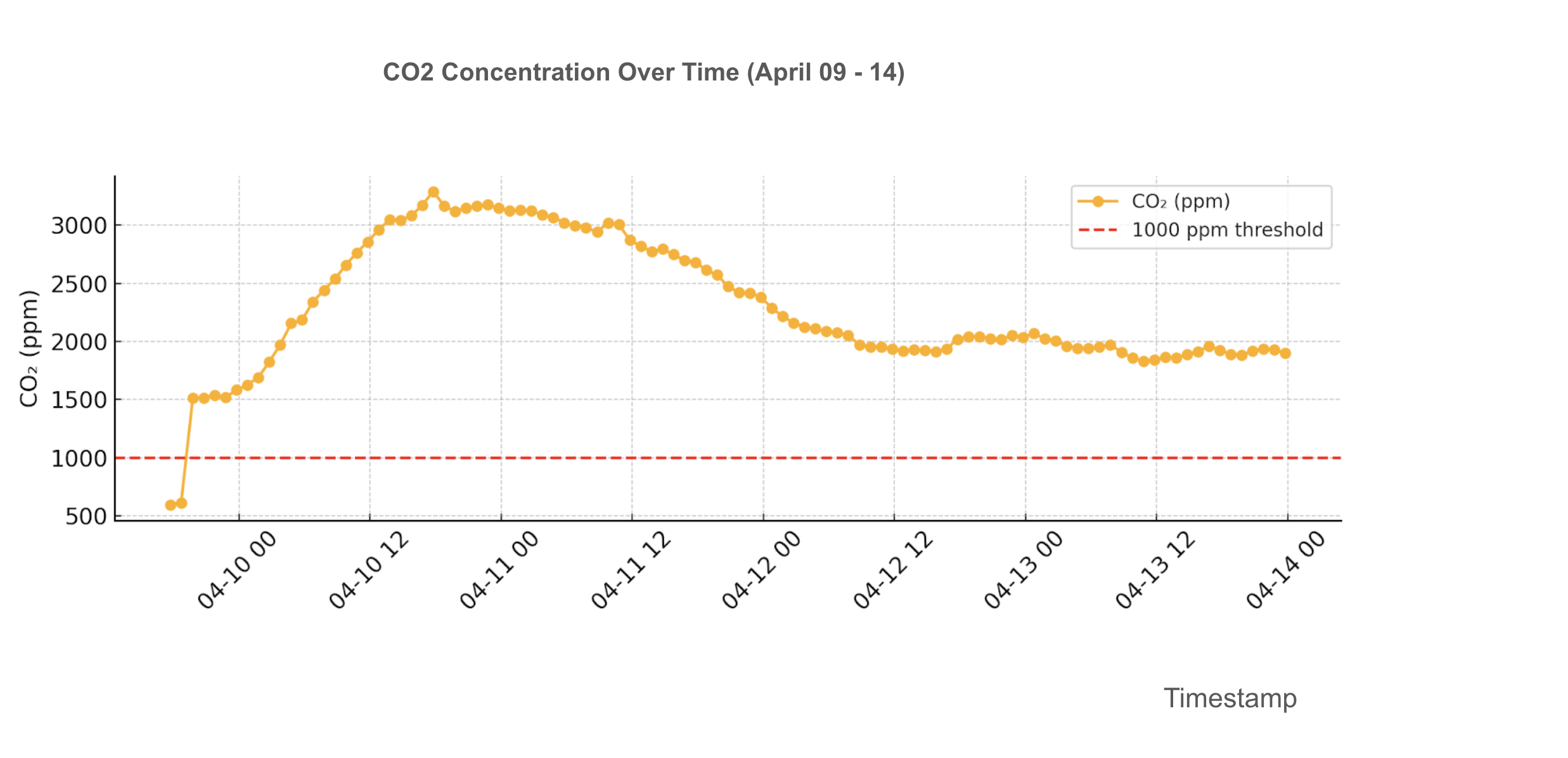

A monitoring system was built with a carbon sensor and an infrared camera. The general code timestamps the growth while recording carbon emissions, temperature, and humidity every hour over the course of 7 days.

The acoustic module formwork remains in the incubator during this 7-day period, growing inside the monitored chamber. At the end of the process, all time-stamped images and logged data become accessible for review.

During the monitored growth phase of the mycelium (April 09–14), environmental data indicated a stable and supportive incubation environment: temperature ranged between 23.0–24.2°C, humidity stabilized near 60%, and CO₂ concentration peaked above 3000 ppm before gradually declining. This rise in CO₂ reflects active fungal respiration during colonization, confirming the biological vitality of the material.

While short-term carbon emissions are recorded during active growth, they do not undermine mycelium’s net carbon-negative profile. As a living organism, mycelium functions as a carbon sink, absorbing CO₂ from the atmosphere and storing it in its biomass. Unlike conventional materials such as cork or PET felt—which require extraction, refinement, and long-distance transportation—mycelium can be grown on-site using upcycled agricultural waste and minimal energy inputs, eliminating the embedded carbon cost of shipping and handling.

A full life cycle assessment (LCA) reveals that the total CO₂ absorbed during growth and production far exceeds emissions from fabrication, use, and end-of-life processing. As such, mycelium-based materials—used for acoustic panels—offer a carbon-negative, low-impact alternative to synthetic or imported bio-based products, exemplifying regenerative material practices in both process and outcome.

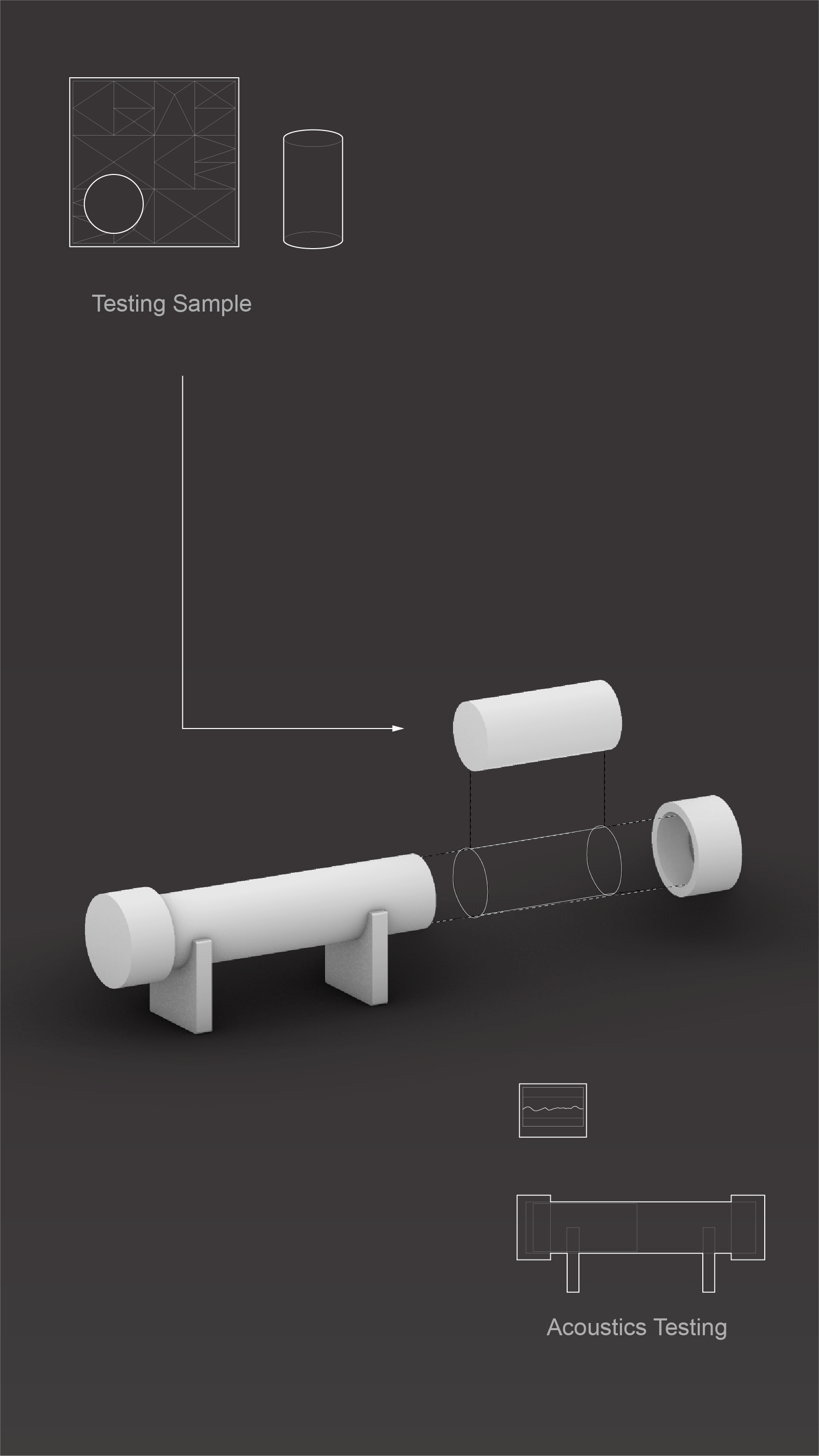

THREE: Testing the Final Prototype

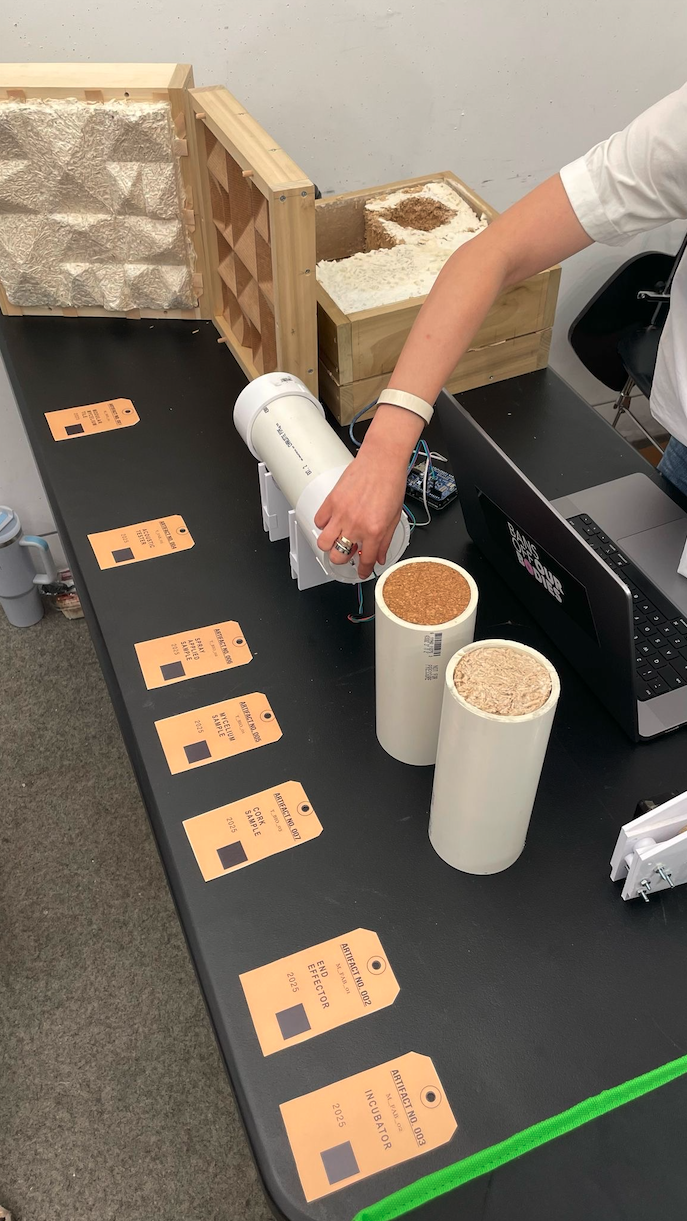

A testing kit was designed using a vacuum tube with a speaker and a sound receiver (sensor) to measure the sound-dampening performance of the prototype. An Arduino Uno was used with a WAV shield to run the setup.

The three samples—mycelium, cork, and SONA spray—fabricated into uniform cylindrical forms to ensure consistency in testing. These bio- and bio-based materials were evaluated in a controlled acoustic setup designed to measure sound-dampening performance across a numerical scale from 0 to 1000.

The test, conducted using a directional sound tube and internal receiver, revealed that all three materials performed within a similar absorption range, landing consistently between 580–600. This outcome underscores mycelium’s competitiveness as an acoustic material when compared to industry-standard alternatives like cork and spray-on cellulose products.

What distinguishes mycelium is not only its acoustic performance, but also its environmental profile: it is carbon-negative, locally grown, and eliminates the need for extraction or long-distance transport. This positions it as a sustainable alternative to conventional materials like cork and spray-based treatments.

DIY Aspect

This methodology introduces a decentralized, time-bound system for producing acoustic building components through controlled biological growth. Requiring approximately 5 to 7 days, the process is cost-efficient and utilizes a bio-based (hemp) substrate, supporting material circularity through upcycling.

Its compact footprint allows deployment in domestic or small-scale environments without specialized infrastructure, positioning it as an accessible fabrication model. By enabling individuals to participate directly in the production of architectural components, the project reframes construction as an open, distributed, and materially regenerative practice.

For a more technical breakdown, see Transformative Automation: Augmenting Robotics Tool for Transformative 3D Modeling.

CORE Value

…there are no new ideas. There are only new ways of making them felt—of examining what those ideas feel like being lived…[5].

— Audre Lorde

This project proposes a participatory, open-source framework that enables designers to pursue individualized outcomes through diverse methodologies. It centers adaptability—not only in form and process, but as a mindset—encouraging variation and embracing experimentation as a mode of learning and making.

Lorde’s words shift the focus from invention as novelty to invention as lived experience. In this light, mycelium—grown rather than made—embodies a regenerative, responsive, and relational material logic. Similarly, computation is reframed as a medium for inquiry and transformation—not merely technical, but cultural and systemic—aligning with the ethos of Computational Design Practices.

This prototype was developed by Julia Kwon as part of my Capstone project for the Master of Science in Computational Design Practices (M.S. CDP) at GSAPP, Columbia University, under the guidance of David Benjamin, Seth Thompson, Laura Kurgan, Violet Whitney, William Martin, Catherine Griffiths, Snoweria Zhang, and Adam Vosburgh.

Special thanks to James Nanasca, Dan Taeyoung, Danil Nagy, Daniel Leithinger, Yonah Elorza, Ryan Luke Johns, Mario Giampieri, Zach Cohen, Celeste Layne, Rebecca Nagaele, Mika Tal, Cedric Steiger—and a very special thanks to Roland Busenhart and Andre Van Belkom for continued support since the Taliesin days.

References

Project Inspiration

Kassel Institute for Sustainability Design. Mycelium Composites for Architectural Applications. University of Kassel, 2023. https://www.uni-kassel.de/uni/en

Ecovative Design. Mycelium Materials and Grown Packaging Innovations. 2024. https://ecovative.com

Arup. Foresta: Exploring Mycelium as a Building Material. 2023. https://www.arup.com/projects/foresta

Elise Elsacker. Publications on Mycelium-Based Design and Fabrication. https://www.eliseelsacker.com/publications

Technical Reference

ScienceDirect. “Impedance Tube.” Engineering Topics. https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/engineering/impedance-tube

Design Reference

CW&T. Ice Cream Shelf. 2022. https://cwandt.com/products/ice-cream-shelf?variant=197876702

Enzo Mari. Autoprogettazione?. Edizioni Corraini, 1974. https://www.corraini.com/en/autoprogettazione.html

Amorim Cork Composites. “Cork Acoustic Panels: Performance and Life Cycle.” Technical Data Sheet, 2022. https://www.amorimcorkcomposites.com ↩︎ ↩︎

ICC Evaluation Services. “ESR-1233: SONASPRAY Acoustical Spray.” International Code Council, 2023. ↩︎

University of Kassel. “Mycelium Composites for Architectural Applications.” Institute for Sustainability Design, 2023. https://www.uni-kassel.de/uni/en ↩︎

SONA. “Bio-Based Acoustic Strategies for Low-Impact Interiors.” SONA Design Report, 2024. https://sona.ac ↩︎

Lorde, Audre. Sister Outsider. Crossing Press, 1984. ↩︎